| | NEWS

"You went after me in a desert, an unsown wasteland" (Isaiah)

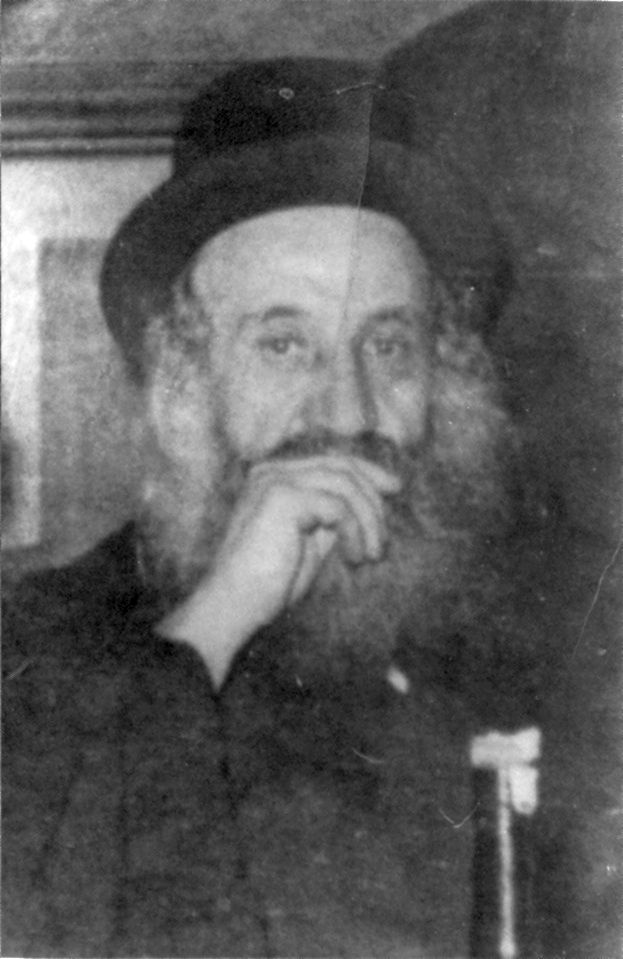

The story of HaRav Moshe Yehuda Schneider, zt'l, rosh yeshivas Toras Emes in Memel, Frankfurt, and London

by M. Samsonowitz

Part V

For Part IV of this series click here.

For Part VI of this series click here.

Rav Schneider was truly among the main disseminators of Torah in our times. An unusual and dynamic individual who transplanted Torah and made it flourish in spiritual wastelands where no one believed it was possible, he did the painstaking groundwork that enabled the barren atmosphere in England and France to give way to the dozens of yeshivos, religious institutions and frum communities that are in existence today.

HaRav Schneider was a man whose entire focus was in the yeshivos which he established, and in his love for Torah, for which he lived. In keeping with his modest personality, his accomplishments for Torah were perhaps not fully appreciated in his lifetime. But the love for Torah and mussar which he instilled in his students produced mighty fruits which changed the face of postwar Jewry in Europe and Eretz Yisroel.

He was expelled from Germany as a Polish citizen, but was not able to leave. His son, HaRav Gedaliah, arranged for leading rabbonim in England to pressure the British Home Secretary to allow HaRav Schneider into England. Once there, he again established a yeshiva and worked to disseminate Torah.

*

Early Students

Rav Moshe Sternbuch: "My mother had asked Rav Lazar Lopian about Rav Schneider's yeshiva. When he told her that the level of learning there was the same as in Telz before the war, she readily agreed to send me.

"Our physical conditions were poor. We never had butter, only margarine. Frequently, the yeshiva ran out of money and we didn't know where our next meal would come from. The bochurim were sent by Rav Schneider to collect from different baalebatim when another of the frequent crises cropped up. We didn't mind because of the tremendous spirit of the yeshiva. Rav Schneider himself was living on next to nothing; he shared everything he had with the bochurim, and treated us like his own sons.

"Once he gave me a list of people to visit, and paid for a taxi to send me to their homes. After spending long hours going from one to the other, I had nothing to show for it. I returned to the yeshiva, ashamed that I had failed. Not only I had brought back nothing, I had even wasted the cost of the taxi.

"When Rav Schneider walked into the beis hamedrash and saw me, he approached me cheerfully. `Ah, Moshe! Thanks so much! You did a wonderful job!'

"`But Rebbe,' I replied dolefully, `I failed! I brought back nothing!'

"`Moshe,' he answered, exuding confidence. `Just this morning a man walked in and gave 25 pounds to the yeshiva. You did your part. How we get the money is Hashem's!'"

*

Fifty years later, a grandson of Rav Schneider's in Israel was tutoring a young English boy learning in an Israeli yeshiva. The young boy's father came to visit his son, and dropped by to visit the tutor. "I was visiting with Mr. Luntzer [a wealthy Jewish businessman from London]," he recounted, "when Rav Schneider sent a student to collect money for his yeshiva. The maid announced the bochur and he soon appeared at the doorway.

"`OK,' Mr. Luntzer mumbled. `Tell Rav Schneider I'll send money soon.' But the bochur didn't move.

"`Well, what is it?' asked Mr. Luntzer impatiently. `Isn't that good enough?'

"The bochur cleared his throat nervously and replied, `There was just enough money for my fare here. Rav Schneider said I should pay my fare coming back with the money that Mr. Luntzer gives me.' "

*

The yeshiva was given day-old bread from Grodzinski's bakery in the East End for free. But the bread had to first be brought to the North End by one of the boys.

A Hungarian bochur called Moshe Reichman was in charge of seeing to it that the bread arrived. It was the hardest task to do in the yeshiva. No bochur wanted the humiliation of carrying a sack of day-old bread on his back in the bus and then for a 15-minute walk to the yeshiva's kitchen. The young fellow found it easier to do the unpleasant job himself than to find takers for it.

"Moshe," Rav Schneider comforted the young man, "In the merit of doing this you will one day provide for the whole Torah world!" Moshe Reichman later moved to Toronto, and the brocho was fulfilled. Be'ezras Hashem it will continue to be fulfilled.

Once the yeshiva was established and flourishing, a Jewish magnate from England approached Rav Schneider. "I know that you are having great difficulties in keeping your yeshiva going," he told him magnanimously. "Don't worry—I'll make a committee, we'll cover your expenses and you'll be able to teach without any worries."

Rav Schneider turned down this generous offer flat. "I know all about these committees," he explained himself afterwards. "They soon start dictating how to run your yeshiva and whom to accept. That's the beginning of the destruction of a yeshiva."

He refused to undertake any arrangement, no matter how attractive, that would leave the decisions in his yeshiva in any hands but his own, despite the heavy financial burden it placed on him. He didn't even ask tuition from parents. "If you ask a parent for tuition, he feels himself a yachson!"

A Father Of Orphans And Refugees

If his work in setting up the yeshiva weren't enough, Rav Schneider turned his attention to the Jewish children—many of them orphans and refugees—who were abandoned in London when Jewish citizens left for the countryside. Concerned for their spiritual welfare lest they end up in gentile hands, he established a boarding school for them within the space of three days. Responsibility for this school was given over to his son R' Gedaliah.

He did the same when he saw young Jewish refugee girls who had arrived in London and were without a shelter. He founded a hostel for them, whose costs were covered by the wages they earned at their jobs. He used to come to speak for them once a week, and worked to find them appropriate shidduchim. Many of the young women there married talmidei chachomim, which was far from the norm at that time.

Yesodei HaTorah Girls' School in London

When Jewish families began to return to London, there was need for a Talmud Torah for their children. Although the public schools were open, the afternoon Talmud Torahs had all been closed down and their staffs had dispersed. Undaunted, Rav Schneider set about founding a Jewish school for these students. This school was to eventually become Yesodei HaTorah, the Jewish day school that provided undiluted Torah chinuch in Stamford Hill in the decades after the war.

To attract more students to Torah, Rav Schneider undertook a bold initiative. He sent his students to local public schools at the hour when studies finished and the children came out. His students located the Jewish students and asked them if they would be interested in attending a Jewish school. Rav Schneider would speak with the parents of interested children about switching their child to the Jewish school. In this way, hundreds of Jewish youths ended up receiving a Jewish education, and some of them later went on to yeshiva.

He drummed into the bochurim that at a time, one may not live for himself. "Don't think only of yourself — give yourself over to Klal Yisroel!"

And indeed, a high proportion of his students became roshei yeshivos, dayanim and mechanchim. Among his prominent students from the yeshiva in England are:

Rav Tuvya Weiss, a dayan in Antwerp and later Gavad in Jerusalem,

Rav Binyomin Zeev Kaufman, rav in Manchester,

Rav Moshe Schwab, mashgiach of Gateshead yeshiva,

Rav Shammai Zahn, rosh yeshiva of Sunderland yeshiva,

Rav Naftali Friedler, rosh kollel and rosh yeshiva in Gateshead, New York City and Toronto and Monsey,

Rav Chonon Karnowski, principal of Manchester boarding school,

Rav Binyamin Pelz, rav in Lucerne,

Rav Avrohom Rand, rosh yeshiva of Mesivta Talmudical College in London,

Rav Ben Zion Rakov, rosh yeshiva of Yeshivas Chayei Olam in London,

Rav Betzalel Rakov, rav of Gateshead, England

Rav Ezriel Shechter, rav and dayan in London,

Rav Moshe Schloss, rosh yeshiva in Yeshivas Tangier and Yeshivas HaRama in London,

Rav A. Silber, head of beis din of kashrus in Jerusalem,

Rav Chatzkel Silber, rosh kollel in Rabinov's Kollel, London,

Rav Dov Sternbuch, Senior Lecturer in Gateshead Seminary,

Rav Moshe Sternbuch, rav and dayan in Johannesburg, and dayan of the Eida HaChareidis of Jerusalem.

Imprisonment Of German Students

There were new trials daily. The English authorities looked askance at this foreign institution which seemed to be inculcating its students with impractical, heaven-oriented aspirations when earthly blood, sweat and tears seemed to them to be the need of the hour. While a rabbinical college may have merit, it wasn't doing anything obvious to contribute to the war effort.

An official was dispatched to suggest to Rav Schneider that his students join the war effort and lay their studies aside temporarily. The official was immediately dismissed.

But the authorities wouldn't give up. Rav Schneider's students were called in and asked pointblank why they weren't contributing to the war effort. One student honestly replied — to their incredulity, "I am helping— by studying Torah."

They questioned him further, "Look—your parents are no longer alive and there will be no one to take care of you. If you go to work, you'll be able to maintain yourself and have food."

The youth replied flippantly, "Well, there will always be people who will work and keep us going."

The officials were aghast. "This boy is obviously mad; Rav Schneider is filling his mind with such ideas."

They issued an order that Rav Schneider must leave London and disband his yeshiva. Rav Schneider responded by calling a fast day, and swiftly getting in contact with Chief Rabbi Hertz. The officials agreed to see Rav Schneider on Friday to review the decision, but Rav Schneider refused to go since he had a longstanding resolution that Friday was to be a yom kodosh, free of all secular concerns. Chief Rabbi Hertz had no choice but to go for him. He managed to convince the authorities that the boy they had questioned had personal problems, and the decree against Rav Schneider was rescinded.

When the authorities began the wholesale imprisonment of German nationals after the conquest of France in 1940, forty German bochurim in the yeshiva were also whisked away. In the various camps where they were sent, they kept up the yeshiva's sedorim. Some of the bochurim were placed on boats and sent to Canada and Australia. Of these, loneliness and uncertainty gnawed away at some; for lack of a study framework others began to work; and others, who were supported by refugee organizations, found it difficult to motivate themselves to self study. From afar, Rav Schneider sought them out, and gave them a boost. In one letter he sent, he wrote,

"Your last letter reached me and broke my heart. Now is not a time to worry; gird your loins like a stalwart man and call your friends together to make a yeshiva! You are eleven bochurim. You can form an outstanding yeshiva that will be an example to Canadian and American Jewry. Rent a flat, small or big—even if there are only two rooms. With the help of G-d, I'll pay the rent. Arrange shiurim, infuse the tefillos with enthusiasm, learn mussar, make a group. It doesn't matter that you don't have a dean or mashgiach. Avrohom Ovinu was three when he recognized his Creator. He lived in the period of Nimrod, the king who threw him into a fiery furnace—but he couldn't be moved. He built an altar to Hashem again and again... You have with you bochurim who are tzadikim, with sharp minds ... each one is more precious than precious... You can make a yeshiva that will be unique in the entire world...

"If you want, I can submit a request to the government that you be permitted to come here. Both in spiritual matters as well as physical matters, more is available here. S. just became engaged, and he founded a yeshiva ketana. About 40 boys are studying in his yeshiva and he makes an honorable living and has a good name.

"M. just got married; he makes a good living and is quite pleased with how things have turned out for him. The other bochurim are living quite comfortably too. But until the petition is granted for you to come here, don't sit there doing nothing, not for even one second! Were I to have wings like a dove, I would fly to help you set up a new place for Torah study."

*

To another bochur he wrote,

"You are extraordinarily talented, and also G-d-fearing! The Chofetz Chaim wrote that the Rambam was hiding away for 11 years in a cave, in danger from the ruler, and there he wrote his Yad Chazaka. The Rambam writes himself at the end of the Mishnayos of Oktzin that his commentary to the Mishnayos was written while wandering and fleeing from one place to another during a time when annihilation was decreed for Jews.

"How much more so can you open up a yeshiva, great in quality even if it be small in quantity... Look what I am doing here. Here I am, a broken plate, without intelligence or strength, a simple person like me. And you, all talented and brilliant, imagine what you could build!"

*

Problems mounted on all sides. It was a day-to-day mind boggling effort to gather funds to keep the yeshiva going.

Even in personal matters Rav Schneider was preoccupied. His second daughter had long ago reached marriageable age, and there was no one he considered suitable for her to marry. Even among the refugees in London who had studied in the European yeshivos, he couldn't find one after his heart. Good friends and advice givers in London repeatedly advised him that he could not compel his daughter to remain unmarried indefinitely. It would be better if she settled with a fine Jewish man who was not particularly learned. "Reb Moshe," they said in exasperation. "It's war time! Are you waiting for Hashem to drop you a chosson from Heaven? Face reality!"

A Chosson Dropped From Heaven

One wintry day in 1941, a ship docked at the London port. This was a special boat, the only one that had reached London in many months. On it was a large selection of English and Allied diplomats who were being exchanged for a similar consignment of Axis power diplomats. This ship had started its long journey two and a half months before, in Shanghai, and had slowly inched its way through the Indian Ocean and around the Cape of Good Hope, on a course to America.

The ship docked in London and proceeded on to Scotland from where it planned to continue on to the U.S. Suddenly Pearl Harbor was attacked and the U.S. was pulled into the war. That was the end of the ship's plans to continue on to the U.S.

This unexpected news filled one particular passenger with dismay. R' Zeidel Semiatitzky was the only Jewish refugee aboard the ship. He had managed to come aboard through the aggressive intervention of a Polish government-in-exile diplomat.

Rav Semiatitzky was one of the lions of the exiled Mir yeshiva. A seasoned chavrusa of Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, even before the war he was famous throughout the Eastern Europe yeshivos for his sharpness and diligence.

When the war broke out, he, together with Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, was involved in managing the Mir Yeshiva's affairs as it made its way through Russia and Japan to Shanghai. In a desperate bid to acquire visas and financial aid for the yeshiva, he had secured for himself a place on the diplomats' boat and intended to reach Canada, where he hoped to arouse government officials and other influential people on the yeshiva's behalf. Suddenly, from being a devoted agent of rescue for the most illustrious yeshiva in the world, Rav Semiatitzky found himself an unknown refugee on the English coast.

Emerging from customs with little more than himself, he searched a phone book for the word "Rabbi" and dialed one of the names listed there. A starched reverend answered the phone, and, quickly sizing up the stranger's Yiddish, directed him to Harry Goodman, a dedicated member of Agudas Yisroel in England.

Mr. Harry Goodman, was an Aguda activist with whom he had corresponded for several years.

A taxi brought Rav Semiatitzky to the proper address during a blackout at night. He banged on the door, "Please open up! My name is Semiatitzky, and I just arrived on a boat from Shanghai!"

Mr. Goodman opened the door, perturbed. This man was obviously a little off, he was sure. How can anyone spin such a tale, let alone hope that anyone will believe it? Just got off a boat? Who does he expect to swallow this yarn? Everyone knows that no boats have reached England in months!

"That can't be!" he replied. "Rav Zeidel is in Shanghai!"

To his good fortune, an old Kamenitz student happened to be visiting Mr. Goodman. "It is Rav Zeidel!" he affirmed.

Mr. Goodman gestured for the stranger to return. After a few minutes' conversation with the famed stranger, the Kaminetz bochur apprised Mr. Goodman, "Do you know whom you almost sent away?"

A message was sent to Rav Schneider that a Mir Yeshiva alumnus had arrived in town. Rav Schneider sent one of his advanced bochurim to check the man out in Torah learning. This student came back intoxicated with the scholar's brilliance. It seemed like Heaven was once again answering Rav Schneider's prayers, this time in high style!

It wasn't a simple shidduch. This illustrious scholar of the Mir Yeshiva had not just come of age. He suffered from a heart ailment that was a result of having rheumatic fever as a child.

There were many who advised the young woman against marrying such a man, despite his positive qualities. Rav Schneider looked at his daughter for an answer. Schneider-style, she shyly replied, "If it's good for the yeshiva, I'll marry him!"

When she became better acquainted with the distinguished man, she declared, "Better to be married to someone like this for ten years than 50 years with another man!"

Rebbetzin Semiatitzky would later say about herself, "Be careful with your words!" When her husband passed away 14 years later, she suddenly realized that, minus the years he had spent abroad for the yeshiva's sake, she had spent exactly ten years of married life with him.

No one could understand it. How did Rav Schneider get the best fellow in the Mir for a son-in-law — and in the middle of the War yet! It was the kind of miraculous intervention that happened weekly for Rav Schneider because of his total subservience to His Creator and Torah study. He annulled his will before his Creator's so his Creator fulfilled his will.

Tefillah in the yeshiva

In Frankfurt, when he founded his yeshiva, none of the bochurim were used to davening the yeshivish manner. They davened at the same speed as their fathers, who had to rush off to work in the morning. Rav Schneider thus remained the only one who davened slowly and carefully. Rav Schneider carefully guided the bochurim to change by buying them siddurim from Vilna with special additions, and giving them to each bochur as a present.

He spoke highly of the commentary of the Rivetz, and the halacha and mussar sections which appeared in the book. He explained how to pronounce the dageshim and mesogim that appeared in the siddurim. When, some time later, he served as a shliach tsibur, he called over a few bochurim and gave them an impromptu shiur on the niggun used in yeshivos. The other bochurim soon caught on, and—without official announcement—the yeshivish davening became the rule.

All the years, Rav Schneider made it his habit to sit at the side of the beis hamedrash during tefillah. He did this partly for practical reasons: to make sure that the quick daveners weren't tempted to finish fast so they could return to Torah study, to keep an eye on the stragglers who might be tempted to come late, and to make sure everyone would respond to the Amen's. He somehow managed to engage in an absorbing tefillah himself while watching what was going on with the talmidim.

Rav Schneider's fiery tefillah was renowned. Never once did any of his talmidim recall him coming late to minyan, but what impressed them even more was the heartfelt outpouring which typified his tefillos. He would unabashedly cry out in the middle of davening: "Tatte! Tatte! Rachmonus!" oblivious as to who was watching or hearing. He recited each word of tefillah like a businessman counting his money. His Boruch Hu uboruch Shemo and Amen seemed to shake the foundations of Heaven.

He insisted that davening must be done from an open siddur instead of by heart. He demanded that each one give his total absorption to the prayers being recited at hand.

It wasn't possible for a bochur to come to daven in the yeshiva after Ashrei, because what would the Rebbe say when he saw him walking in so late! To speak in the middle of chazaras hashatz or Kaddish was an indefensible sin. No one, not even the most diligent learners in the yeshiva would go unrebuked after such a lapse.

Avodas Hakodesh

One concept which he emphasized to his students was "Avodas Hakodesh." Every person is demanded by halacha to give ma'aser. What if a person has no money to give, like a bochur in yeshiva?

Rav Schneider answered - A person has to give 1/10 of whatever he does have. If he only has time, he has to give ma'aser of his time. So Rav Schneider would conscript the older bochurim to teach younger bochurim, to solicit parents to send their children to Jewish schools, and to do a myriad of tasks that took away from their Torah learning but which was a required part of their Jewish obligations.

|